by Kenneth Perez | Nov 12, 2025 | Business

Here on Meditation Mountain, we often talk about mindfulness in its traditional sense: the silent cushion, the focus on the breath, the gentle observation of our thoughts. This practice is the bedrock of a peaceful mind.

But what if your path to inner calm looks a little different?

For many of us, the command to “clear your mind” can feel like an impossible task. The more we try to silence our thoughts, the louder they become. The good news is that true mindfulness isn’t just about emptying the mind—it’s about focusing it.

And for many, the purest form of focus is found in the “flow state.”

The Geek’s Meditation

The flow state is that magical, almost spiritual, place where you are so deeply immersed in an activity that the rest of the world fades away. Time seems to distort. Your sense of self dissolves into the task at hand. It’s a state of high-focus, single-pointed awareness.

And where do we find this state most often? In the passionate, complex pursuits we often call “geeky.”

- A programmer, lost in lines of code, solving a complex problem.

- A mathematician, mapping out an elegant proof.

- A scientist, deep in research, connecting disparate data points.

- A gamer, fully immersed, reacting with split-second instinct.

This is not zoning out; it is zoning in. This is mindfulness in action. When you are in this state, you are not worrying about the future or ruminating on the past. You are profoundly, completely present.

Living Your Truth: Authenticity as Mindfulness

A core part of any mindfulness practice is discovering and accepting our authentic selves. We meditate to peel back the layers of who we think we should be, to find the person we truly are.

But this discovery is only half the journey. The other half is living that truth. For many, this means embracing the passions that define them. It means being proud to be a nerd, a geek, a creator, or a thinker. When your hobbies and your identity are in alignment, you reduce internal friction and find a natural state of peace.

Wear Your World

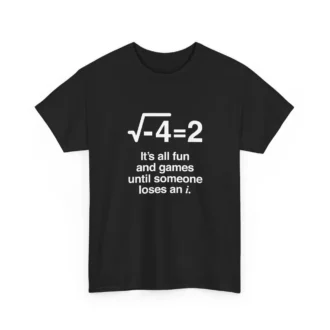

Expressing this authentic self is a joyful and mindful act. It’s a way of telling the world, “This is who I am, and I love it.”

This can be as simple as the clothes we choose to wear. A t-shirt, rather than just being a piece of fabric, can become a small, joyful celebration of your true self. We recently found a wonderful online store called Geek T Shirts Company that truly understands this. They create clever, high-quality nerd shirts for coders, scientists, and math lovers that are less about flashy logos and more about a witty, shared “secret handshake.” So, whether your meditation is on a cushion or in front of a keyboard, the goal is the same: find your focus, and celebrate your authentic self.

by Kenneth Perez | May 23, 2025 | Business

When planning a memorable family vacation, the fundamental choice often comes down to two distinctly different but equally enchanting landscapes: the sun-drenched beaches of a tropical island or the majestic peaks of a mountain retreat. Both offer unique experiences and a chance to reconnect, but which one is truly right for your family’s next adventure?

Let’s explore the charms of a sprawling Bali family villa versus the cozy comfort of a mountain chalet.

The Allure of the Alpine Chalet

Mountain chalets evoke images of warmth, rustic elegance, and thrilling outdoor activities.

-

Cozy Comfort: Imagine crackling fireplaces, plush throws, and stunning views of snow-capped peaks or lush forests. Chalets offer an intimate, hygge-filled atmosphere, perfect for board games and hot cocoa after a day out.

-

Adventure Awaits: Skiing, snowboarding, hiking, mountain biking, and exploring charming alpine villages are typical activities. The crisp, clean air and panoramic vistas provide a dramatic backdrop for active families.

-

Seasonal Beauty: From vibrant spring blossoms to golden autumn foliage and pristine winter snow, mountain regions offer a dynamic beauty that changes throughout the year.

However, mountain chalets might mean less predictable weather, limited swimming opportunities (unless there’s an indoor pool), and sometimes a feeling of being a bit more “off-grid.“

The Enchantment of a Bali Family Villa

Now, picture yourself in a in family vila in Bali. It’s a world away from the mountains, offering a different kind of luxury and adventure.

- Tropical Grandeur & Space: Bali villas are renowned for their expansive layouts, often featuring multiple pavilions, lush private gardens, and stunning swimming pools. This offers abundant space for families to spread out, play, and relax without feeling cramped.

by Kenneth Perez | Mar 24, 2025 | Business

In countries like Thailand, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Laos, Theravāda monks have long served as custodians of ancient meditation practices. Rooted in the earliest teachings of the Buddha, their approach often emphasizes mindfulness (sati) and concentration (samādhi) through practices such as ānāpānasati (mindfulness of breathing) and vipassanā (insight meditation). Many monks in these traditions spend years or even lifetimes in quiet forest monasteries, engaging in intensive daily meditation and silent retreats. They also frequently teach laypeople through temple visits, public talks, and meditation centers, helping to spread the discipline of mindfulness beyond monastic walls.

Theravāda meditation is known for its simplicity and clarity, focusing on observing thoughts, emotions, and sensations with non-judgmental awareness. This style of meditation has been widely adopted in the West through retreats and programs led by Southeast Asian monks or their Western disciples.

Tibetan Buddhist Monks and Visualization Practices

Tibetan Buddhism, practiced widely in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of northern India, is rich in symbolic rituals and visual meditative techniques. Tibetan monks often engage in practices such as shamatha (calm abiding) and tonglen (sending and receiving), as well as more advanced visualizations involving deities, mandalas, and sacred syllables. These methods are designed not only to calm the mind but to transform it, encouraging compassion, wisdom, and the realization of one’s inner nature.

Teachers such as the Dalai Lama and other revered Tibetan lamas have played a central role in bringing Tibetan meditation to global audiences. While some methods require deep initiation, many Tibetan monks also offer basic mindfulness and compassion practices that are accessible to beginners of any background.

Zen Monks and the Art of Stillness

Zen Buddhism, which flourished in Japan after originating in China as Chan, emphasizes seated meditation (zazen) and direct, experiential understanding of reality. Zen monks live lives of strict discipline, often in silent monasteries where meditation, work, and daily tasks are all considered part of the path. The simplicity of Zen—sitting in stillness, observing thoughts, and letting them pass—contrasts with more elaborate systems, but is equally profound.

Zen teachers stress the importance of presence and direct experience over intellectual study. Many Western Zen centers today follow the guidance of Japanese or Korean Zen monks who have shared these teachings around the world. Their focus on simplicity, silence, and breath resonates with those seeking a clear, grounded approach to meditation.

by Kenneth Perez | Feb 24, 2025 | Business

The concept of the “third eye” has existed for thousands of years across many spiritual and philosophical traditions. Often associated with the space between the eyebrows, this mystical inner eye is believed to be a gateway to higher consciousness, intuition, and spiritual insight. In Hinduism, it is connected to the Ajna chakra—one of the seven main energy centers in the body—and is said to govern clarity of thought and inner vision. In Buddhist iconography, enlightened beings are often depicted with a symbolic third eye, representing their awakened state. Meanwhile, ancient Egyptian texts refer to the “Eye of Horus,” which some interpret as a symbol of spiritual perception and protection.

Though different cultures describe it in varied ways, the common thread is that the third eye represents a deeper kind of seeing—not with the physical eyes, but with the mind or soul. In meditation, awakening the third eye is often a metaphor for becoming aware of subtler aspects of experience and gaining greater insight into oneself and the nature of reality.

The Role of the Ajna Chakra in Meditation

In yogic traditions, the third eye is closely linked to the Ajna chakra, located in the center of the forehead. This energy center is believed to be the seat of intuition, wisdom, and imagination. When this chakra is balanced and activated, individuals may experience enhanced focus, a sense of inner calm, and even moments of spiritual clarity or vision. Meditation practices that focus on the Ajna chakra often involve visualizations, silent concentration on the forehead area, or the repetition of mantras like “Om”—a sacred sound believed to align the mind and spirit.

Some meditators also use crystals, such as amethyst or lapis lazuli, to help stimulate this area, or engage in breathwork exercises designed to direct energy to the third eye. These practices are not meant to create supernatural experiences, but rather to deepen awareness and cultivate a more intuitive, centered state of being.

Awakening Awareness, Not Escape

While the idea of opening the third eye can sound mysterious or even mystical, in practical terms it’s about becoming more present and observant. It’s not about escaping reality, but about seeing it more clearly—beyond distraction, fear, or illusion. Meditation that focuses on third-eye awareness encourages people to step back from habitual thinking and observe their inner landscape with honesty and curiosity.

By tuning into this deeper sense of perception, meditators often find a greater connection to their inner guidance, a clearer sense of purpose, and an ability to navigate life with more clarity and compassion.